When my daughter and son-in-law offered us a month on their Sausalito houseboat while they vacationed in Germany, Tom and I jumped at the chance to escape the three-digit heat of mid-summer in Calaveras County. We would also care for their ninety-pound silver lab named Ash, whom I love. During the third week I scheduled a long overdue cataract surgery.

The morning after the operation on my left eye, I rolled slowly out of bed and tried to find my footing. The houseboat seemed to move even though the surface of the bay was like glass. I gingerly pulled off the tape holding a plastic cup over my eye, and walked out onto the deck to look at the world. Sunlight painted a streak of cerulean blue below heavy gray clouds with luminous edges, reflected in the water. It was shockingly beautiful. I went into the bathroom and peered into the mirror. What I saw was not beautiful. I had aged ten years overnight and looked like the crone mask I sculpted after turning sixty.

The morning after the operation on my left eye, I rolled slowly out of bed and tried to find my footing. The houseboat seemed to move even though the surface of the bay was like glass. I gingerly pulled off the tape holding a plastic cup over my eye, and walked out onto the deck to look at the world. Sunlight painted a streak of cerulean blue below heavy gray clouds with luminous edges, reflected in the water. It was shockingly beautiful. I went into the bathroom and peered into the mirror. What I saw was not beautiful. I had aged ten years overnight and looked like the crone mask I sculpted after turning sixty.

Wrinkles I hadn’t seen before fanned out around my mouth and eyes as if etched with the fine tip of a Crow quill pen while I slept. Raccoon eyes looked back at me reproachfully, “What did you expect?” A quote from First Corinthians 13 came to mind. “For now we see through a glass darkly, but then face to face.”

This is obviously not what the apostle Paul had in mind, but it fit perfectly. I’d been trying to see through the darkening screen of cataracts for several years. I needed to look face to face at myself becoming old. Aging with your eyes wide open is what my book, BURNING WOMAN, is about.

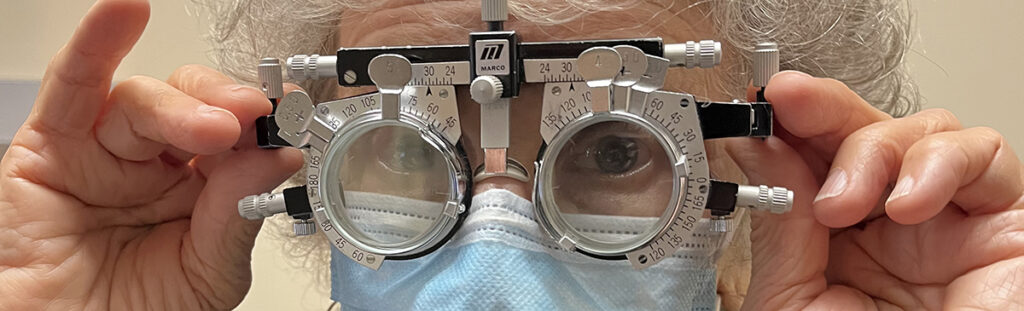

I wasn’t apprehensive on the drive to the surgery center. Everyone I knew who had the operation said it was fast and relatively painless. The patient gets a local anesthesia, the clouded lens is removed, and a clear artificial lens is implanted. In fifteen-minutes, it’s done.

At the hospital, a nurse greeted me with a smile as if she was a flight attendant welcoming me onboard and led me to a row of beds that looked like an assembly line with patients awaiting their turn for the operating table. She handed me a paper gown to put on over my clothes, took my vitals, and asked the routine questions. The anesthesiologist popped in and said I would be awake during the procedure. No worries. I’d feel no pain.

I was wheeled into an operating room the size of a large broom closet, sandwiched between my surgeon and his assistant. They had begun prepping for surgery when I heard two people animatedly discussing a car crash one of them had been in. “Is that my anesthesiologist?” I asked. “Please tell them to stop talking.” I heard a contrite “sorry” and the room got quiet. After the anesthesia took effect, all I sensed was my eyeball being probed and two small spheres of light.

Post op I was given eye drops, a clear plastic patch, and a cup of apple juice. My eye hurt like hell. I have a pretty high pain threshold, but this was intense. When I told the nurse, she said not to be concerned, patients sometimes feel discomfort, and then she whisked me out the door to Tom, who was waiting in the car.

Before he turned on the ignition I said, “I can’t drive home like this. My eye feels like a hot coal. Something’s wrong!”

He took one look at me, found a wheel chair in the lobby, and took me up the elevator to the front desk. “We need help.”

Without looking up from her screen, the receptionist said, “I’ll be with you in a minute.”

Tom said, “NO! My wife is in pain and we need the doctor! You don’t want to see me angry!”

The startled woman looked up at all six feet six inches of my knight in shining armor and said, “I’ll call right now, sir. He may be in surgery but I’ll get him.”

Within minutes, my doctor took us into his office and measured two times the normal pressure in my eye. He did a quick procedure to relieve it, and gave me drops to ease the pain.

The second surgery three days later was similar, but the hot coal didn’t burn as much. I wasn’t surprised by feeling that my right eye might explode and I had drops to treat it. I knew what to expect.

I had to wait a month for my eyes to heal before receiving a new prescription for glasses. That was a problem. Although surgery corrected my nearsightedness, it couldn’t fix strabismus, a condition that makes me see double without corrective prism in the lenses. How would I drive to work the week we returned home? I got temporary glasses which prevented me from veering off the two-lane road when my eyes tired, but sometimes I had to close one eye to see straight.

Finally, I got a perfect pair of electric-blue-framed glasses that corrected my strabismus. Leaving LensCrafters into the flash and glitter of Arden Mall in Sacramento was like being inside a video game. The visual stimulation was psychedelic. Colors vibrated. Everything was in sharp focus and alive in a way I hadn’t experienced in years. The intensity softened on the drive home. Like a child, I looked at the world passing by in wonder.

Yet, I was exhausted by this journey from what had been years of increasingly obscured vision to the ordeals of surgery and finally reconnection with absolute clarity to the visual world. The surgery was a success and the physical recovery was over, but a residue of melancholy remained.

Looking in the mirror for the first time the morning after surgery, I saw a woman in her eighties. It was like a time warp. I was in my own sci-fi horror film, as if I had lost ten years of my life overnight. This can’t be. I’m not ready for this. I want more time!

I forced myself to look in her eyes…to find me in her face. It was more terrifying than the cataract surgery. But, gradually my breathing relaxed and I understood. This gift of clear vision had a dark side. Part of my recovery was loving the woman in the mirror.

Dear Sharon

Acceptance of how we age takes time and while blurry vision takes away the wrinkles—clarity allows us to see the beauty of ourselves and the world.

When I had cataract surgery a few years ago, I was astonished with what I had been missing—individual leaves on trees and the blue, blue sky with clouds. And, yes, my new old self!

Thanks, Sharon. I really enjoyed the unveiling. And I’ve been there. Warmly, Summer

Dear, dear Sharon, Thank you for lighting the way for us! I’m sorry it was such an ordeal, but grateful that you came out of it so well. Way to stick to your principles and find the rewards. It’s not easy.

I’ve gone back and re-read this one, Sharon. With recent losses and my own aging, mortality is certainly on my mind more these days. I’m celebrating your newly clear vision, in spite of the challenges, and hope you have been getting up to some wonderful things lately!